Sue “Them” In Their Personal Capacity

The laws are intended in part to act as a deterrent to criminal acts. But laws lose…

The world of law is full of tricks, traps, word magic, word art and outright deceptive practices.

The world of law is full of tricks, traps, word magic, word art and outright deceptive practices.

Are you shocked? I didn’t think so.

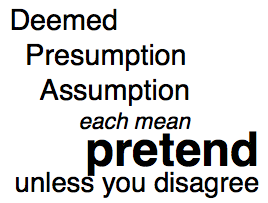

Presumptions are one of those tricks which can be somewhat reasonable, at times, but often used for evil purposes. Presumptions, assumptions and to “deem” something, all mean “let’s pretend“.

Unfortunately to the honest, average man this means “its decided” when in reality it is an invitation by the legal wordsmiths inviting you to act to defeat their pretending and therefore end the game, but most people don’t. 🙁

Since almost every legal action is based on this “let’s pretend” game. The power is in your hands to say no, let’s not play a game.

This short video focuses on the presumption of jurisdiction by “Canadian authorities” via the Canada Evidence Act, Section 30 “Business records to be admitted in evidence” relating to “performing a function of government” using a unique definition of “business” for this section of this Act only.

“Business” is usually general in nature with “no specific legal meaning”. But the Canada Evidence Act (CEA) has a redefined “business” for one purpose…defining business records.

If you’ve studied statute construction principles and legal word magic your spidey senses should be tingling.

Black’s Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, defines “presumption” as follows:

A presumption is a rule of law, statutory or judicial, by

which finding of a basic fact gives rise to existence of

presumed fact, until presumption is rebutted. … A legal

device which operates in the absence of other proof to

require that certain inferences be drawn from the available

evidence.

You must remember that their case is built on MANY presumptions and each presumption you should challenge them to prove. Including the definition of “business” if your activities were private in nature and not related to “business” under the CAE…..

Canada Evidence Act Section 30

Business records to be admitted in evidence

30. (1) Where oral evidence in respect of a matter would be admissible in a legal proceeding, a record made in the usual and ordinary course of business that contains information in respect of that matter is admissible in evidence under this section in the legal proceeding on production of the record.

….

Canada Evidence Act Section 30 Definitions

(12) In this section,

“business”

« affaires »

“business” means any business, profession, trade, calling, manufacture or undertaking of any kind carried on in Canada or elsewhere whether for profit or otherwise, including any activity or operation carried on or performed in Canada or elsewhere by any government, by any department, branch, board, commission or agency of any government, by any court or other tribunal or by any other body or authority performing a function of government;

It appears that one of the presumptions always made is that everything you do is governed by statute law, which really means that the basic presumption is that the government can tell you what you can and cannot do because they “own” you.

If that doesn’t seem quite right/fair, I agree, and so do all freedom loving folks around the world.

Make Sure CHECK out this latest powerful info:

Authority and Jurisdiction to Make and Enforce Laws…Comes From OWNERSHIP

So, if it really is not right/true, it must be a legal presumption, an assumption, or deemed to be fact, which means it isn’t but the courts will pretend it is true/fact, until you challenge it.

Your option when faced with any deem/presumption/assumption/legal conclusion is to challenge the party making it to prove it is a fact. The party making the claim (presumption) must prove it when challenged.

Any evidence you do provide to prove the presumption false can also work….although the burden is rightfully on them, not you, to prove everything they claim — if you challenge it.

Do your own investigation. What do you think the CEA section 30 and definition of “business” mean? Check out the video BELOW for a walk through of the concept.

Read about the “law of presumption” HERE for starting your further research.

Hope this makes sense and helps!

Canada Evidence Act

http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/stat/rsc-1985-c-c-5/latest/rsc-1985-c-c-5.html

Case Cited as Example

Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Skomatchuk, 2006 FC 730 (CanLII)

R. v. Dell, 2005 ABCA 246 (CanLII) – Charter, private person & “performing function of gov’t”

Application of the Charter to Interactions Between Private Citizens

[6] Although s. 32 of the Charter limits its application to Parliament, legislatures and provincial and federal governments, when the Charter was first introduced there was some debate about its application. Since that time, the law has been settled that, as a general rule, the Charter only applies to government actions, not interactions between private citizens or institutions: Schreiber v. Canada (Attorney General), 1998 CanLII 828 (SCC), [1998] 1 S.C.R. 841 at para. 27; McKinney v. University of Guelph, 1990 CanLII 60 (SCC), [1990] 3 S.C.R. 229 at para. 182. Recently in R. v. Buhay, 2003 SCC 30 (CanLII), [2003] 1 S.C.R. 631, 2003 SCC 30 at para. 31, the Supreme Court confirmed that for Charter purposes, private security officers are no different than other private citizens, noting that “while private security officers arrest, detain and search individuals on a regular basis, the exclusion of private activity from the Charter was not a result of happenstance. It was a deliberate choice which must be respected.”

[7] Buhay, supra, recognized two exceptions to the general rule that the Charter does not apply to interactions between private citizens. The first is when a private citizen acts as an agent of the state: Buhay at para. 25 citing R. v. Broyles, 1991 CanLII 15 (SCC), [1991] 3 S.C.R. 595. The agent of the state analysis requires an examination of the relationship between the state and the private individual alleged to have acted as an agent of the state. To decide whether the bouncer in this case was an agent of the state, the relevant question is: Would the exchange between Dell and the bouncer have taken place, in the form and manner in which it did take place, had the police not intervened? See Buhay at para. 25. This question must be answered in the affirmative because the detention and search of Dell were independent from any police activity or instruction. The police did not become involved until they responded to a call following Dell’s detention and search in the washroom. Accordingly, the bouncer was not acting as an agent of the state and the Charter does not apply on this basis.

[8] The second exception to the general rule that the Charter does not apply between private individuals occurs when a private person can be categorized as “part of government” because he or she is performing a specific government function: Buhay at para. 25, citing Eldridge v. British Columbia (Attorney General), 1997 CanLII 327 (SCC), [1997] 3 S.C.R. 624. In Eldridge, at para. 43, the Court noted that the Charter will only apply to a private entity if it is found to be implementing a specific governmental policy or program. The Court in Buhay, at para. 31, observed that this exception would apply if there were an express delegation of a public function to a private person or if the state were to abandon, in whole or in part, an essential public function to the private sector.

NOTE: This post is the first in a series of quick TIPS to explore concepts that are key to understanding the law and your rights. If you like it, let us know below. Feel free to leave your feedback about what we missed, or maybe misinterpreted.

Email us if you would like us to address a legal concept that stumps you.

[64] The issue turns upon the meaning attributed to the word “deemed” in s. 3(3) of the Bankruptcy Act. Does it mean “deemed conclusively” or “deemed until the contrary is proved”?

[65] Section 3 provides:

3. (1) For the purposes of this Act, a person who has entered into a transaction with another person otherwise than at arm’s length shall be deemed to have entered into a reviewable transaction.

(2) It is a question of fact whether persons not related to one another within the meaning of section 4 were at a particular time dealing with each other at arm’s length.

(3) Persons related to each other within the meaning of section 4 shall be deemed not to deal with each other at arm’s length while so related. [emphasis added]

[66] In R. v. Verrette,1978 CanLII 208 (SCC), [1978] 2 S.C.R. 838, 3 C.R. (3d) 132, 40 C.C.C. (2d) 273, 85 D.L.R. (3d) 1, 21 N.R. 571 [Que.], Beetz J. said at p. 15:

A deeming provision is a statutory fiction; as a rule it implicitly admits that a thing is not what it is deemed to be but decrees that for some particular purpose it shall be taken as if it were that thing although it is not or there is doubt as to whether it is.[emphasis added]

[67] As noted in Hickey v. Stalker, 53 O.L.R. 414, [1924] 1 D.L.R. 440, the appellate division of the Supreme Court of Ontario construed “deemed” as used in s. 8(4) of the Mechanics Lien Act as “deemed until the contrary is proved”. Middleton J. noted that the word “deemed” has several different meanings and ” ‘has acquired no technical or peculiar signification where used in legislation, but like other words, must be interpreted with reference to the whole Act of which it forms a part.’ ” He held that “deemed” as used in the Mechanics Lien Act should ” ‘be treated as prima facie evidence'”, ” ‘until the contrary is proved’ ” to save the legislation from being unjust. He noted at p. 445:

That it is the duty of the Court, in seeking the true legislative intention of an Act, which undoubtedly is the sole duty of the Court, to regard the possible consequences of alternative constructions of ambiguous expressions, has been determined in many cases.

“What, then, is to be done? We must try and get at the meaning of what was intended by considering the consequences of either construction:” Brett, L.J., in Re R.L. Alston(1882), 8 P.D. 5, at p. 9. If one construction will do injustice and the other will avoid the injustice, “it is the bounden duty of the Court to adopt the second and not to adopt the first of those constructions:” Lord Cairns in Hill v. East and West Indian Dock Co.(1884), 9 App. Cas. 448, at p. 456. “where there are two meanings each adequately satisfying the language” (of the statute), “and great harshness is produced by one of them, that has legitimate influence in inclining the mind to the other … It is more probable that the Legislature should have intended to use the word in that interpretation which least offends our sense of justice:” …

http://www.canlii.org/eliisa/highlight.do?text=%22rebuttable+presumption%22&language=en&searchTitle=Search+all+CanLII+Databases&path=/en/bc/bcca/doc/1989/1989canlii2747/1989canlii2747.html

Another case dealing with “presumption” vs “inference”:

-end-In using the term “presumption”, the Crown did not use it as connoting an inference that may but need not be drawn from the evidence, but rather as pointing to an inference that must be drawn as to the presumed fact—here the required detriment—on proof of a basic fact—here the acquisition of a complete control of a business in a market area.

[Page 425]

I do not think that it is open to a court in a criminal case to raise a presumption such as is contended for by the Crown in this case in the absence of legislative direction. Inference as part of the logical process of deduction from proved facts is one thing; a rebuttable presumption of law has the effect of altering the burden of proof which, if there is no legislative prescription to the contrary, rests on the Crown with respect to every element of an offence charged against an accused.

http://www.canlii.org/eliisa/highlight.do?text=%22direct+inference%22&language=en&searchTitle=Search+all+CanLII+Databases&path=/en/ca/scc/doc/1976/1976canlii146/1976canlii146.html