It’s a Start At Least: Police Accountability

These two news stories caught my eye for different reasons. We have had a spate…

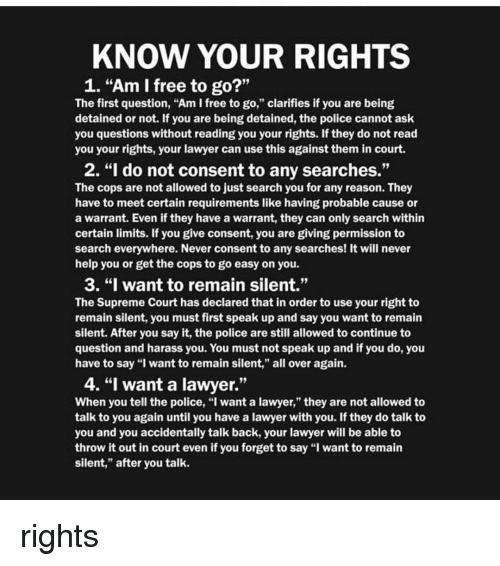

When even lawyers tell you not to talk to police and people on the street start using “I don’t answer questions” in response to police talking to them…what is up?

There is a saying “he who is asking questions is in charge and the one in authority”. I guess you need to decide: do you maintain/hold your authority or allow someone else to take it from you?

Here are some youtube videos of lawyers saying don’t talk and examples of people responding with “I don’t answer questions”. Always be polite and respectful, maintain your respectful authority which demands respect.

.

Check out this video on Authority

Especially note the VOLUNTARY disclosure of the fact he was in a fight and the even more damning VOLUNTARY disclosure that had drugs on him when the officer only had just cause to frisk for weapons and was only asking about any more weapons….a big mouth leads to a drug charge and conviction.

Probably 90% of arrests and convictions are made based on voluntary disclosure by the party involved…

Common law jurisdictions will have similar rules around searches, the principles are pretty much the same. (bold and red emphasis mine)

STATE v. MICHELSON

THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE,

v.

GLENN MICHELSON.No. 2009-386.

Supreme Court of New Hampshire.

Argued: March 24, 2010.

Opinion Issued: May 7, 2010.

Michael A. Delaney, attorney general (Thomas E. Bocian, assistant attorney general, on the brief and orally), for the State.

David M. Rothstein, deputy chief appellate defender, of Concord, on the brief and orally, for the defendant.

DALIANIS, J.

The defendant, Glenn Michelson, was found guilty, based upon stipulated facts, of possession of diazepam, a controlled drug. See RSA 318-B:2, I (2004) (amended 2008). He appeals an order of the Superior Court (Arnold, J.) denying his motion to suppress evidence seized as a result of a stop for a motor vehicle violation. We affirm.

The trial court found or the record of the suppression hearing supports the following. On or about the evening of February 1, 2007, Sergeant Stan Andrewski of the Claremont Police Department stopped the defendant after observing him make two turns without signaling. In addition to the defendant, there were two passengers in the vehicle. Andrewski asked the defendant to step out of the car, which he did. The defendant had blood on his face and nose and said that he had been involved in a fight.

Detective Brent Wilmot arrived to assist, and spoke to the defendant at the rear of his cruiser. While the defendant was telling Wilmot about the fight, Wilmot saw Andrewski remove a baseball bat from the defendant’s car. Wilmot asked the defendant why he had the bat, and the defendant explained that he carried it to defend himself in the event of an attack, which he had reason to fear based upon recent phone calls he had received. Wilmot believed that the defendant “was not being 100 percent truthful” due to his lack of eye contact, failure to answer questions directly, and attempts to change the topic. Wilmot then asked the defendant if he had any other weapons. The defendant replied that he “didn’t think so.”

Wilmot informed the defendant that he was going to do a pat-down search for weapons. During the frisk, Wilmot found a small folding knife in the defendant’s pocket. He then asked the defendant whether he had “anything else on his person.” The defendant stated, “To the best of my knowledge, I don’t have anything.” Wilmot replied, “What does that mean?” and the defendant said, “There shouldn’t be anything.” Not convinced of the defendant’s truthfulness, Wilmot asked again, “What, if anything, you know, do you have on you?” The defendant then admitted that he had drugs and produced two diazepam tablets wrapped in cellophane from the coin pocket on his right hip.

Before trial, the defendant moved to suppress the diazepam, arguing that the search of his person violated his rights under Part I, Article 19 of the New Hampshire Constitution and the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Following a hearing, the trial court denied the motion. On appeal, the defendant argues that the trial court should have granted his motion because Wilmot did not have a justifiable basis for performing the frisk. In the alternative, he argues that even if the frisk was justified, Wilmot’s subsequent questions impermissibly expanded the scope of the stop.

We first address the defendant’s argument under the State Constitution, State v. Ball, 124 N.H. 226, 231-32 (1983), and cite federal opinions for guidance only, id. at 233. In reviewing the trial court’s ruling, we accept its factual findings unless they lack support in the record or are clearly erroneous. State v. McKinnon-Andrews, 151 N.H. 19, 22 (2004). “The application of the appropriate legal standard to those facts, however, is a question of law, which we review de novo.” State v. Roach, 141 N.H. 64, 65 (1996).

“Once an officer is justified in making an investigatory stop, he may also conduct a protective frisk if the officer reasonably believes the individual is armed and presently dangerous.” State v. Szcerbiak, 148 N.H. 352, 355 (2002) (quotation omitted). “[T]he purpose of a protective frisk is not to discover evidence of a crime, but to allow the officer to pursue his investigation without fear of violence.” Roach, 141 N.H. at 67 (quotation omitted). “Therefore, the frisk must be strictly confined to what is minimally necessary to discover the presence of a weapon.” Id. (quotation and brackets omitted).

The defendant does not dispute that he was lawfully detained as a result of his motor vehicle violation. See McKinnon-Andrews, 151 N.H. at 23; Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 22 (1968). He argues that Wilmot was not justified in performing the frisk because he had no reasonable suspicion that the defendant was armed and dangerous. We disagree.

“To determine the sufficiency of an officer’s suspicion, we consider the articulable facts in light of all surrounding circumstances, keeping in mind that a trained officer may make inferences and draw conclusions from conduct that may seem unremarkable to an untrained observer.” State v. Joyce, 159 N.H. 440, 446 (2009) (quotation omitted). “A reasonable suspicion must be more than a hunch,” and “[t]he articulated facts must lead somewhere specific, not just to a general sense that this is probably a bad person who may have committed some kind of crime.” Id.(quotations omitted). “The officer’s suspicion must have a particularized and objective basis in order to warrant that intrusion into protected privacy rights.” Id.(quotation omitted).

Here, the defendant stated that he had been involved in a fight and had blood on his nose. A baseball bat, which he admitted to carrying for self-defense, was found in his car. Based upon the defendant’s behavior, including his lack of eye contact and unclear response when asked whether he had any other weapons, Wilmot doubted the defendant’s truthfulness in responding to his questions regarding the fight. In particular, Wilmot suspected that the defendant might have been the assailant in the fight. Wilmot believed that his safety was at risk as he spoke to the defendant. In view of these facts, Wilmot had a reasonable suspicion that the defendant was armed and dangerous, and he was justified in assuring himself that the defendant did not possess a weapon by conducting a protective frisk. See Roach, 141 N.H. at 67;United States v. Hanlon, 401 F.3d 926, 930 (8th Cir. 2005) (noting that one factor supporting suspicion that defendant was armed and dangerous was the defendant’s refusal to make eye contact with a police officer); 4 W. LaFave, Search and Seizure: A Treatise on the Fourth Amendment § 9.6(a), at 627-28, 630 (4th ed. 2004) (discovery of a weapon in a suspect’s possession is a circumstance weighing in favor of upholding a frisk). Because the Federal Constitution is no more protective of the defendant than the State Constitution under these circumstances, see Roach, 141 N.H. at 67; Arizona v. Johnson, 129 S. Ct. 781, 784 (2009), we necessarily reach the same conclusion under the Federal Constitution.

The defendant next argues that even if the frisk was lawful, Wilmot’s questions impermissibly expanded the scope of the stop. We disagree.

“An investigatory stop may metamorphose into an overly prolonged or intrusive detention (and, thus, become unlawful).” State v. Turmel, 150 N.H. 377, 383 (2003) (quotation omitted). Whether the detention is a lawful investigatory stop or goes beyond the limits of such a stop depends upon the facts and circumstances of the particular case. Id. During a legal investigatory stop, an officer may ask the detainee a moderate number of questions to determine his identity and to try to obtain information confirming or dispelling the officer’s suspicions. Szcerbiak, 148 N.H. at 355. The scope of a stop, however, must be carefully tailored to its underlying justification — to confirm or to dispel the officer’s particular suspicion.Id.; McKinnon-Andrews, 151 N.H. at 23.

To determine whether the scope of a permissible stop has been exceeded, we examine whether: (1) the question is reasonably related to the initial justification for the stop; (2) the law enforcement officer had a reasonable articulable suspicion that would justify the question; and (3) in light of all the circumstances, the question impermissibly prolonged the detention or changed its fundamental nature.McKinnon-Andrews, 151 N.H. at 25.

If the question is reasonably related to the purpose of the stop, no constitutional violation occurs. If the question is not reasonably related to the purpose of the stop, we must consider whether the law enforcement officer had a reasonable, articulable suspicion that would justify the question. If the question is so justified, no constitutional violation occurs. In the absence of a reasonable connection to the purpose of the stop or a reasonable, articulable suspicion, we must consider whether in light of all the circumstances and common sense, the question impermissibly prolonged the detention or changed the fundamental nature of the stop.

Id. (quotation and brackets omitted).

Although the purpose of the initial stop concerned the defendant’s violation of a traffic law, when the defendant told Andrewski that he had been involved in a fight, the purpose of the stop became, in addition, an investigation into the fight. When Wilmot arrived on the scene, he was directed to investigate the circumstances of the fight. Wilmot’s particular suspicion was that the defendant may have been the assailant in the fight. Questions regarding whether the defendant had any additional weapons on his person were reasonably related to this purpose. Accordingly, no constitutional violation occurred.

To the extent that the defendant argues that we should interpret Wilmot’s questions as asking whether he had other items on his person besides weapons, we disagree. In its order denying the defendant’s motion, the trial court implicitly found that Wilmot’s questions pertained only to weapons, and we cannot say that such a finding lacks support in the record or is clearly erroneous. See State v. Silva, 158 N.H. 96, 102 (2008) (court assumes that trial court made all findings necessary to support its decision). Indeed, Wilmot specifically stated at the suppression hearing that he “didn’t have any reasonable suspicion to think that” the defendant had “any drugs or contraband,” indicating that his questions were limited to weapons.

The Federal Constitution provides no greater protection than the State Constitution under these circumstances, see McKinnon-Andrews, 151 N.H. at 27; Muehler v. Mena, 544 U.S. 93, 100-02 (2005). Accordingly, we reach the same result under the Federal Constitution.

Affirmed.

BRODERICK, C.J., and DUGGAN, HICKS and CONBOY, JJ., concurred.

http://www.leagle.com/unsecure/page.htm?shortname=innhco20100507331